Hildegard of Bingen: visions of divinity.

A history of pantheism* and panentheism by Paul Harrison.

Featured, Dec. 12, 1996.

Featured, Dec. 12, 1996.

Are you a pantheist? Find out now at

Scientific Pantheism.

Are you a pantheist? Find out now at

Scientific Pantheism.

I, the fiery life of divine essence, am aflame beyond the beauty of the meadows, I gleam in the waters, and I burn in the sun, moon, and stars.

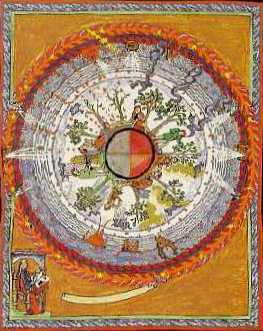

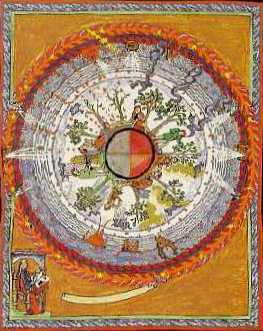

Vision of the earth. Miniature by Hildegard (seated at bottom).

Hildegard of Bingen was born in 1098, to a family of minor German nobility. As the tenth child, she was dedicated to the church, and sent to an anchoress, Jutta, for education. When Jutta died in 1136, Hildegard was elected head of the small convent at Disibodenberg. She moved to Bingen on the banks of the Rhine in 1150, where she administered a convent and a monastery. She died in 1179 at the age of 81.Throughout her life, beginning as a young child, Hildegard had visions. But it was not till her early forties that she began to have the symbolic and didactic visions for which she became famous. At first she wrote nothing down, but when she fell seriously ill, she blamed this on the decision not to reveal her visions. After consulting with the pope and St Bernard of Clairvaux, she began to write the visions down and publish them.

She wrote several books, including The Book of Life's Merits (1150-63); The Book of Subtleties of the Diverse Nature of Things (1150); and (most famously) The Book of Divine Works (1163).

She was a woman of extraordinary and diverse talents - part of that early flowering of culture known as the twelfth century renaissance. She corresponded with bishops, archbishops, popes and kings, and spoke out openly against corruption in the church. She had a broad familiarity with the science of her day - primitive and dogmatic though it was. She often describes the natural world in her books, most often as a symbol or example for some religious point.

Hildegard was also a gifted poet, writing plainchant songs in vibrant Latin. Today she is best know for the ethereal music to which she set her verse, in echoing voices which soar up and down the scales like angels singing in full flight.

Hildegard painted too - records of her visions, showing herself as a tiny seated figure with an open slate or book, gazing upwards at huge symbolic mandalas of cosmic processes, full of angels and demons and winds and stars (see image above). The paintings have simple patterned borders, naive figures, and schematic arrangements. They are reminiscent, in a different style, of the paintings of William Blake and Samuel Palmer.

Her visions were quite detailed, and she also claimed to hear words, spoken in Latin. She saw them in her soul, not with her bodily eyes, which remained open. She often saw a brilliant light - more brilliant than a cloud over the sun. Inside this light she sometimes saw an even brighter light which she called "the living light." This made her lose all sadness and anxiety.

Like all mystics she experienced total loss of self during her visions: "I do not know myself, either in body or soul. And I consider myself as nothing. I reach out to the living God and turn everything over to the Divine." [Letter to Wilbert of Gembloux, 1175]

Her visions also seem to have been accompanied with pain and fainting fits:

"From the very day of her birth," she writes of herself, "this woman has lived with painful illnesses as if caught in a net, so that she is constantly tormented by pain in her veins, marrow and flesh. This vision has penetrated the veins of the woman is such a way that she has often collapsed out of exhaustion and has suffered fits of prostration that were at times slight and at other times most serious." [Book of Divine Works: Epilogue]Recently Charles Singer and Oliver Sacks have interpreted these physical symptoms as migraine attacks. One of her visions was of falling stars turning black as they plunge into the ocean. Hildegard interpreted this as the rebel angels falling from heaven. Singer reads it as showers of phosphenes across the visual field, followed by a negative blind spot. Her concentric mandalas and her light with the light are seen as another visual symptom of migraine. But this interpretation, whether accurate or not, takes nothing away from the meaning she or we attribute to her visions.

Hildegard has been canonized by the Creation Spirituality movement of Matthew Fox, a former Dominican priest, now excommunicated. Fox sees her as a precursor of feminism, of acceptance of the body, and of environmentalism.

Certainly she believed that God was present, through the Holy Spirit, in everything. But she also believed that God could never be fully known by living humans. In this sense she was not a pantheist (universe=divinity) but a panentheist - everything is fully in God, but God is not fully in everything.

She viewed the human body and soul as a microcosm, repeating the divine plan and the natural world in miniature. But she was no prophetess of interdependence in the modern sense. The external world and the human body are usually seen, not in their own right, but as symbols of divine and spiritual matters.

Hildegard seems to have some knowledge of sex, whether from her own experience or from counselling her nuns. In this passage she appears to describe a female orgasm:

When a woman is making love with a man, a sense of heat in her brain, which brings with it sensual delight, communicates the taste of that delight during the act and summons forth the emission of the man's seed. And when the seed has fallen into its place, that vehement heat descending from her brain draws the seed to itself and holds it, and soon the woman's sexual organs contract, and all the parts that are ready to open up during the time of menstruation now close, in the same way as a strong man can hold something enclosed in his fist.However, she regarded chastity as far superior. She saw the lusts of the flesh as being in opposition to the soul, and adultery as a heinous sin which would be punished in Hell with toxic odours and smoke.

She does have a positive attitude towards nature. You can't help feeling as you read: this is a woman full of vigour and interest in the world, stulted by a world-rejecting religion so that she is forced to repress her natural desires and turn all her interest in the world into an interest in the way the world symbolizes spiritual matters.

But it's also very clear that she followed an orthodox theology, and believed in angels, Satan, Paradise, and the whole divine scheme of Incarnation, Atonement, Redemption, and Resurrection.

To the last she remained deeply modest, always stressing her lack of education, attributing all the glory to God:

A wind blew from a high mountain and, as it passed over ornamented castles and towers, it put into motion a small feather which had no ability of its own to fly but received its movement entirely from the wind. Surely the almighty God arranged this to show what the Divine could achieve through a creature that had no hope of achieving anything by itself. [Letter to Abbot Philip]The passages below are from Hildegard of Bingen, Book of Divine Works, edited by Matthew Fox, Bear & Company, Santa Fe, 1987.

Selected passages.

Hildegard's panentheism.

The divine essence is present in all things.

[God is speaking:] I, the highest and fiery power, have kindled every spark of life … I, the fiery life of divine essence, am aflame beyond the beauty of the meadows, I gleam in the waters, and I burn in the sun, moon, and stars. With every breeze, as with invisible life that contains everything, I awaken everything to life. The air lives by turning green and being in bloom. The waters flow as if they were alive. The sun lives in its light, and the moon is enkindled, after its disappearance, once again by the light of the sun so that the moon is again revived … And thus I remain hidden in every kind of reality as a fiery power. Everything burns because of me in the way our breath constantly moves us, like the wind-tossed flame in a fire. [Vision 1:2.]God is always in motion and constantly in action. [1:2]

The Holy Spirit, source of all life.

Holy spirit, life that gives life,

moving all things,

rooted in all beings;

you cleanse all things of impurity,

wiping away sins,

and anointing wounds,

this is radiant, laudable life,

awakening and re-awakening

every thing.

[De Spiritu Sancto.]Oh fire of the Holy Spirit,

life of the life of every creature,

holy are you in giving life to forms …

Oh boldest path,

penetrating into all places,

in the heights, on earth,

and in every abyss,

you bring and bind all together

From you clouds flow, air flies,

rocks have their humours,

rivers spring forth from the waters

and earth sweats her green vigour.

[O ignis Spiritus Paracliti]

Sparks from God's radiance.

All living creatures are, so to speak, sparks from the radiation of God's brilliance, and these sparks emerge from God like the rays of the sun … But if God did not give off those sparks, how would the divine glory become fully visible? … For there is no creature without some kind of radiance - whether it be greenness, seeds, buds, or another kind of beauty. [4.11]Every human soul endowed with reason exists as a soul that emerges from the true God … This same God is that living fire by which souls live and breathe. [10:2]

When we know nature, we know God.

It is God whom human beings know in every creature. For they know that he is the creator of the whole world. [2.15]We too have a natural longing for other creatures and we feel a glow of love for them. We often seek out nature in a spirit of delight. [4.105]

Microcosm - macrocosm.

God delineated all of creation in the human species, just as the whole world emerged from the divine word. [4.14]God has inscribed the entire divine deed on the human form. [4:105]

Body and soul are a unity.

Therefore both body and soul exist as a single reality in spite of their different conditions… . Up above and down below, on the outside as on the inside, and everywhere - we exist as corporeal beings. [4:103]

Hildegard's transcendentalism and world-rejection.

God is transcendent.

I am the day that does not shine by the sun; rather by me the sun is ignited. I am the Reason that is not made perceptible by anyone else; rather, I am the one by whom every reasonable being draws breath. And so to gaze at my countenance I have created mirrors in which I consider all the wonders of my originality, which will never cease. [4:105]God cannot be seen but is known through the divine creation, just as our body cannot be seen because of our clothing. And just as the inner brilliance of the sun cannot be seen, God cannot be perceived by mortals. [9.14]

Nature is subject to Humanity.

God has directed for humanity's benefit all of creation … creatures have to serve our bodily needs. It is also understood that they are intended for the welfare of our souls. [3.2]The human species sits on the judgement seat of the world. It rules over all creation. Each creature is under our control and in our service. We human beings are of greater value than all other creatures. [4:100]

We must reject the flesh.

As long as we enjoy the things of the flesh, we can never fully grasp the things of the spirit … Whoever shows devout faith in the divine promise … by scorning earthly things, and by revering heavenly things, will be counted as righteous among the children of God. [1.16]The soul is in opposition to the wishes of the flesh. [4:82]

Sexual desire is the work of the devil.

The voracity of the devil's gullet inspires our loins with pleasure in sinning and fleshly desires in that very place where what we eats descends and is ejected, and where the desire of the flesh is rampant. Yet God's protection has defended our loins and endowed them with chastity by raising up their actions to what is good. [9.4]The right eye of good conscience … considers that the desires of the flesh are without value and do not gaze at the light of truth. Whatever frisks about wildly with indecent actions will afterward be submerged in sorrow. [2.27]

When we live according to our soul's desire, we deny ourselves out of love of God, and become strangers to the lusts of the flesh. [2.47]

PANTHEISM

is a profound feeling of reverence for Nature and the wider UniverseIt fuses religion and science, and concern for humans with concern for nature.

It provides the the most solid basis for environmental ethics.

It is a religion that requires no faith other than common sense,

no revelation other than open eyes and a mind open to evidence,

no guru other than your own self.

For an outline, see Basic principles of scientific pantheism.

Top.

Top.

Scientific pantheism: index.

|

If you would like to spread this message please include a link to Scientific Pantheism in your pages

Suggestions, comments, criticisms to: Paul Harrison, e-mail: pan(at)(this domain)

© Paul Harrison 1997.